Ellie Johnson

Sept. 11, 2001. For Kansas City Fire Department Battalion Chief Larry Young, the day started off how a usual day for an off-duty fireman would. However, what Young couldn’t expect was the events that would follow such a normal early morning. At 8:46 a.m. the day would become historical and never be forgotten by Young and the rest of America.

“Within 30, 40 minutes after the first tower collapsed, we got paged,” Young said.

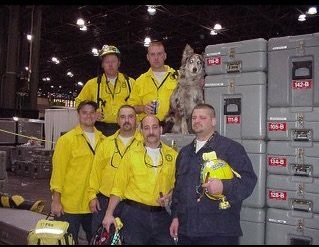

Young, along with at least 62 other firefighters in Missouri, were trained USAR (Urban Search and Rescue) firefighters in September of 2001. USAR is a nation-

wide organization of firefighters who are trained to travel and aid in federal crises in the country’s urban areas. Young was a member of Missouri Task Force One (MOTF-1), whom he said were put on loan to the federal government as Urban Search and Rescue operators.

“We had never been deployed at that point. The Task Force, the 27 federal teams, had not really been utilized much and they were pretty new in their conception,” Captain Chad Dailey said, another member of the MOTF-1 team who was also deployed to Ground Zero. Ground Zero was a term used to describe the ground directly below the explosion of each of the Twin Towers.

The journey to New York for Young, Dailey, and the other USARs began at Whiteman Air Force Base near Sedalia where they flew out on military C-130s.

“The plane was packed. We had to make a [legal] will [and] we had to be sniffed and checked by bomb dogs,” Dailey said.

During their air travel, USAR teams had no access to any outside news. Young said once they were locked onto the aircraft the team’s main objective became to focus on New York and the information they received from the government.

Young and Dailey landed in New Jersey in the late evening of 9/11 where all the military bases were on their highest lockdowns.

The Fire Rescues were then transported int

o Lower Manhattan under armed guard and escorted by highway patrol.

“We could only get within a few blocks of Ground Zero [riding the busses]. Almost every day we walked down to Ground Zero [and] we had to hike several blocks,” Dailey said.

Dailey recalled just how overwhelming the scene in Lower Manhattan was.

“You could not see from one side to the other. Ground Zero was just not a neighborhood block. It was something you couldn’t see over, through, or past. And to walk to another side of it would take you a half an hour,” Dailey said.

“It was dusty forever. There was smoke, there were still a lot of fires going on, dust, all that stuff. You’re looking at a pile that is probably 15, 20 stories tall that used to be two giant buildings,” Young said. “You can train all you want, but as soon as you turn that corner, that first day, and that first street you’re like ‘Holy crap. This is huge.’”

“It was just surreal,” said St. Louis firefighter and MOTF-1 9/11 responder Steve Mossotti in an interview with the St. Louis Public Radio. “Walking in there and standing up on that rubble pile and looking around. There was still smoke. And the upper floors of the building next door were burning still. It was like, ‘All r

ight, I’ve been to hell. I know what hell looks like now.”’

“There was no comparison of what people saw on tv versus what real life was. It was beyond belief the amount of disruption and the amount of death that laid beneath our feet. It’s something that doesn’t leave you,” Dailey said.

Of the 343 firefighters that lost their lives at Ground Zero, all of the FDNY USAR members were gone. Young and the other USARs became a crucial federal asset.

“We worked [searching] for hours. 24, 30 something hours before we got a break,” Young said. When the USAR teams were off-duty, they slept at the Javits Convention Center in lower Manhattan.

“You were supposed to have 12 hours off by the time you traveled down to Ground Zero, got back, got cleaned up, tried to get something to eat, and got to bed. You didn’t end up with 12 hours off. Your shift ended up being 14 hours usually,” Dailey said. “But it wasn’t bad. Most of us would rather be working than trying to sleep.”

Firefighters and rescuers were transported between the convention center and the World Trade Center on buses under armed escort at all times.

Young said, “we [the firefighters] were

kind of locked into the pile. They had fencing around the whole area. When we went back to that convention center, we weren’t allowed to leave the convention center because of the security issues. Everyone was freaking out about what was next.”

“The Pile,” as Young refers to the World Trade Center, became a term to describe the pile of debris and bodies that covered the streets at Ground Zero.

The MOTF-1 stayed in New York searching for almost two weeks, but only ever recovered bodies.

“We try not to ever give up the hope that

we are going to find someone [alive] because in any kind of collapse event you always know there are potentially pockets where people may have been trapped or sought refuge,” Mossotti said. “Unfortunately, we also know that as time goes on the chances of finding survivors goes down, even among individuals who might have survived the collapse. Their chance of surviving quickly goes down after the second and third days,” Mossotti said.

Even 20 years after the destruction of the World Trade Center and the attack on the Pentagon, first responders like Young, Dailey, and Mossotti still believe there were impactful lessons learned during the weeks following the terrorist attack on America.

“You’ve taken an oath to take care of people on their worst day. You have to do what you can do and if you’re not willing to do that, you’re in the wrong line of work,” Young said. “I’ve got a lot of bad memories, but I’ve also got a lot of friends and good things that have come out of it. You’ve just always got to look for the silver lining and keep going forward.”

Dailey said that 9/11 ignited a mortality motivation within him. Ever since that day he said he tries to live his life to the fullest because he acknowledges that he could have been a victim of something like 9/11.

“It’s easy to let things pass and forget the vulnerability of our country,” Mossotti said. “But we always need to keep our guard up and realize that another incident like that can happen at any time. We should never forget the memories of those who sacrificed their lives and the innocent victims killed that day.”